Note: this was one of my early attempts to craft a single travel journal piece from an adventure. Two of my best buddies and I spent eight chaotic, harebrained days in the Middle East in the autumn of 2004. It took me more than ten years to see the opportunity to publish my writing.

Jordan

Waking up in Amman, the capital of Jordan, is like waking up to find that you are blocking a fuel price protest rally. There is such a pandemic of bleating car horns throughout the city that the sound melts down to one sustained, inharmonious note that pervades from dawn until late night. There is a lot of shouting too. Standing on street corners and shouting is something that an Englishman like me struggles to comprehend while much of the rest of the world gets on with it fervently. The cacophony rose throughout the morning as the sun’s heat began to claw at a dirty hotel window by my head. Unable to sleep, I heard myself repeating, with unfading disbelief: “you’re in the Middle East”.

Amman, Capital of Jordan

The infinity of cubist concrete boxes that make up Amman’s houses are draped over several steep jebels and wadis (hills and valleys) so navigation on foot is painfully exertive. If you happen to arrive there during Ramadan but don’t know that you have, and proceed to spend an entire day yomping over the slopes like mountain goats, you have my sympathy. The holy fasting month is the time for a necessary deceleration of life, so a couple of London boys on a marching mission without access to food or water will not last long. Pumice-lipped and sandpaper-tongued, my companion, Joe, and I were desperate for relief while there were still four hours remaining until we could drink or eat. Joe spotted a barber shop suspiciously stowed in a discreet alley halfway up a hillside and suggested a cheap shave to take our minds off the dehydration. I will never adhere to his advice again. Four young men from Baghdad went to our necks and cheeks with sadistic glee, until we were raw and bleeding all over. We were too scared to do anything but smile back and try to make basic conversation. The older of the four held a cut-throat to my adam’s apple and simply said, “Saddam Hussein, good, bad?”

I made a virgin effort at diplomacy with the reply: “George Bush bad”, but the barbers recoiled in synchronised horror shouting, “No! George Bush good!”

“Ah”, I floundered. Must find some safe ground, “good and bad?”

The head barber thought for a moment as his assistants watched for an answer. He was posing with his razor cocked for effect, the blade bulging with white foam and specs of my blood. “In between”, he stated, and discussions were closed without human sacrifice.

We proceeded up steep alleyways to the principle tourist site in Amman, a ruined Roman temple at one of the city’s highest points, where a cooler air blows through pine trees and sandstone columns and where we found solace from a combined state of malnourishment, heat exhaustion and anxiety. Up there the car horns are filtered by the breeze into a quiet background hum and it is easy to feel the centuries fall away with the sound; to mentally superimpose a busy Roman scene throughout the ancient arches and walls. While we sat in dappled shade on a low wall that was older than Christ, an old man sat further down, occasionally tapping his walking stick against his knee. He could have been there since the birth of the universe. The sense of timelessness was so present in the air and the dust and the old man with his stick that our pain vanished and the hours to sunset became a brief and pleasant moment.

Timeless Roman remains above Amman

At official sunset time somebody turns off the music and the whole swinging party stops running around in noisy circles and dives for an empty seat. The viscous traffic flow peters out to a dilute trickle and where there was, minutes earlier, not a bite to eat or a drop to drink, brimming cafés emerge like nocturnal spring flowers. It is eating time and everyone is invited. Strangers will unfold tables in the street, cover them in finger food and invite you to join in. Pittas are stuffed with hummus and sugar is ladled into coffee. The Muslim world stops work and comes together to share in the gorging of empty stomachs. And as quickly as it starts, the scene reverses. The bright cafés wither into darkness and the traffic restarts its raucous mêlée, guiltily covering up the feast as if it never happened.

While Amman wheels in its chaotic dance, Petra, in the south of the country, stands rock still in time and place. Petra is what Jordan wants to be. Everyone who wishes to view the ancient site gets to feel like an explorer, having to approach it from a track at the base of a narrow canyon, just as the Nabateans would have when they carved Jordan’s masterpiece from the sandstone cliffs. At first, one glimpses a sliver of the temple façade through a gap in the canyon walls before reaching an abrupt opening where the curtain finally falls on the 2,000 year-old scene. Early visitors, following a funeral procession for some great priest perhaps, must have been awed to dementia after marching the half-mile or so, flanked by vertical sandstone cliffs which almost but don’t quite touch all the way up for hundreds of feet. Such natural drama needs music, a big, round trumpeting score which would climax just as the canyon ends and the red temple proudly presents itself in the dusty golden sunlight.

First sight of Petra’s main temple between the canyon walls.

Apart from the clichéd complaint that the fat, visor wearing tourist hordes spoil the romance of the place, or that the local tradesmen are hardened to visitors and have become pushy, the only let-down in Petra is a common misconception derived, embarrassingly, from Hollywood. When Indiana Jones rode in to the temple to search the final resting place of the Holy Grail, he arrived at a vast and complex interior. If Harrison Ford had really tried to gallop full steam between the shadowed columns of the temple entrance he would have been hospitalised. There is nothing there: just a small, dark room big enough for a coffin, some flowers, the immediate family in-mourning and maybe a couple of sacrificial goats squeezed in at the back. Don’t be dissuaded from visiting, however. The precision with which the Nabateans carved away the sandstone exterior is mind boggling to behold. And when you get bored of looking at that, there are several more temples, an amphitheatre and the odd broken column here and there to gawp at just around the corner.

We took a brief dip in the Red Sea, a few miles Southeast at the port of Aqaba, before leaving because the industrial city felt too real to be interesting. In a small van we had hired in Amman we played video game driving with the cargo trucks on the highway North. In Jordan, wherever roadwork is in “progress”, the traffic is shoved into the oncoming lanes and left to work things out for itself. There are no rules and there is no point in trying to approach the experience sensibly, it is way too much fun for that. We brushed wing mirrors with forty-ton trucks, undertook speeding fruit vans and dodged spilling oil, grain and machine parts before turning off and climbing an empty road into the sky above the desert, following the Kings Highway, along which Moses had led his people to safety and Richard the Lionheart had led his knights to an expensive slaughter. The winding asphalt fell steeply away through medieval towns, over which castles hung precipitously, the heat built, the brakes started to stink and the shimmering Dead Sea appeared, suspended like silver fog over the desert ahead.

Being overtaken by a fruit truck while already overtaking lorries, all in the oncoming lanes of the motorway

Another friend, Alex; Calamity Al; the Social Hand-grenade, had joined us back in Amman and within no more than thirty seconds of wetting our ankles in the salty curiosity that is the Dead Sea, he had disobeyed the only advice we had been given, and dived headfirst into the brine. Al squealed, squirming like a stuck octopus, unable to rub the salt from his eyes with his wet hands. Joe and I bobbed impossibly high on the buoyant, oily surface and let our muscles forget the previous two nights’ sleep in the van, while Al floated off to be with his wounded self. Perhaps ten minutes later there was a splashing sound, as Al tried to steady himself in the water, followed by fresh screams. I shut my eyes, smiled smugly, laid back and thought of anywhere but England.

Al and Joe, drinking gin & Tango on the banks of the Dead Sea

Syria

Wars and terrorism, or the assumed threat of either, can do wonders for popular tourist destinations. For many years the IRA’s bomb threats did a great job of stemming the haemorrhagic flow of brainless visitors to London, filtering the influx down to only the more adventurous and interesting ones. There was also a time when flocks of blinkered foreigners migrated to Damascus for their holidays but now the city has been blissfully exorcised of the West, by the West. Politics and the media will decide if Damascus will become the next sold-out city of the East, but for now it is safe to walk her market-lined streets without hassle. The stall workers shout “hello, welcome to Syria!” and let you walk on. They might tell you that their shop is the best in town but they will not pester you to stop.

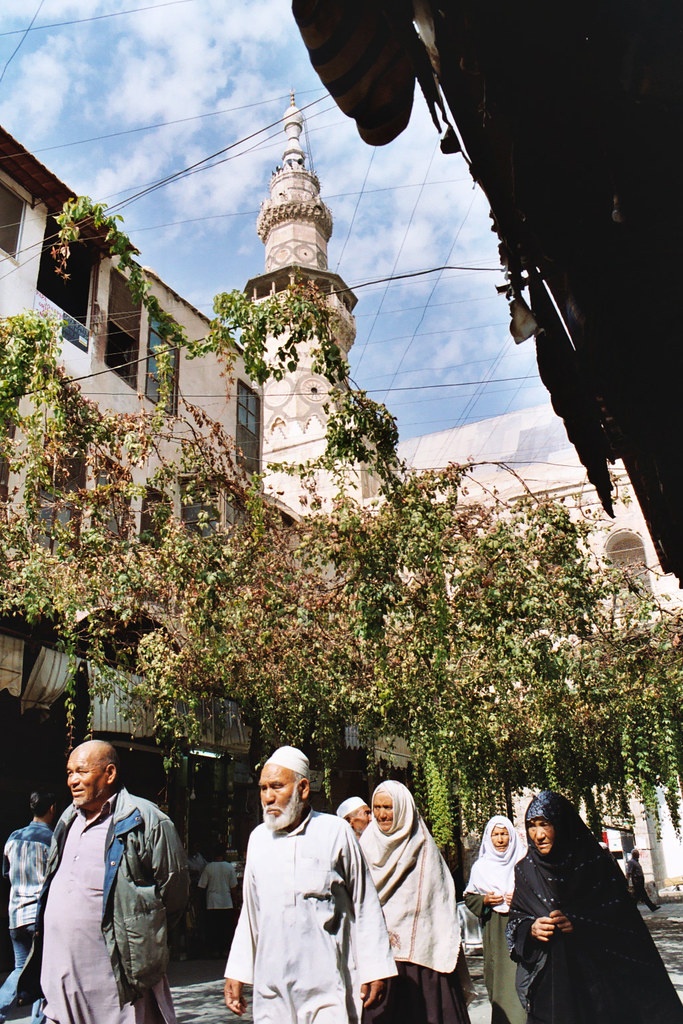

The narrow streets of Damascus

Explorers of Syria’s capital can dodge traffic, haggle over silks and smoke hubblies in the moonlit, ivy creeping Roman streets without worry, until their lungs pack in. Strangers love to meet you and appear genuinely relieved to see western faces roaming the crowded alleyways. Behind this sense of buoyancy and pious fellowship however, masked by the sweet smell of sheesha smoke, is a seething, livid infection on the national psyche: paranoia. It seems that every other man in Syria is a member of the secret police, recognisable either by the way they get cagey when you ask them about their jobs or because they have a 9mm automatic protruding from their beltline. Talk to everyone, make a friend of Syria but never, ever mention in public the holy taboos: Israel and the secret police.

A few hours drive from the capital across the dead yellow earth a spine of low mountains runs parallel with the Mediterranean coast, down into the greener slopes of Lebanon. At its Northern end, just inside Syria, squats the finest of all the castles built by the crusading knights. Brilliantly, most of the work that had been done to make the Krak Des Chevaliers appealing to visitors, from the floodlights to the tour guides, has all but crumbled away to history with the decline of tourism. What is left is one of the most intricate castles you are ever likely to lay your eyes on, bare and unadulterated. There are dark holes to fall down and paths that lead to nothing. The rooms are unlit, so great looming shadows allow the visitor to use their imagination. This is just how it should be. My friends and I stormed the gatehouse in our trainers, beheading imaginary guards with invisible swords, and nobody even noticed.

When the sun set the infinite plateau, over which the castle keeps an eye, tucked itself into a misty quilt and fell asleep to the haunting harmonies of five synchronised muezzin, calling all to prayer from speakers atop the nearby minarets. We ate in a hotel restaurant with 100 covers but only one other guest, then us three exhausted fortress attackers slept in the warm dust on the summit of the hill. A few hours later the holy warbling started again, echoing in the predawn fog. I thought about my friends at home who had sucked through their teeth and felt compelled to ask: “isn’t that dangerous?” when I told them that I was visiting the Middle East. Up there, as the Milky Way lost its command of the sky to a salmon coloured sunrise, and the name of Allah swirled and rode on the thermals rising from the desert below, the foolish words of my friends had no place.

Lebanon

Is there a border crossing in the world that does not feel like a visit to the headmaster’s office? We are invariably forced to listen to wannabe fascists who look like they got where they did by failing police exams, hating their guts but biting our lips. One day, I swear, some sweaty customs chief is going to give me one hundred lines and threaten to tell my parents. Getting from Syria to Lebanon was no different. We had to take three taxis instead of one, because them’s the rules. We had to get a stamp from that guy and a signature from his cousin in the next building, because them’s the rules. Al’s passport was handed up past furrowed brows through the ranks of officers until it fell into the chubby hands of their fearless führer. He played tennis with his grim eyes, bouncing from the image of Al’s face to the identical real McCoy in front of him. I rolled my eyes in boredom and spotted a charming sentiment amidst this farce of fatuous bureaucracy: in the corner of the customs hut a family of birds had made their nest.

Almost disappointingly the headmaster acquitted us without so much as a detention and we were able to get stuck straight back into some good, old-fashioned rule breaking, as our taxi driver embarked on a traffic-dodging expedition worthy of an honorary place in the World Rally Championships. He kept turning back to talk to us, only to receive abrupt, smiling replies which all really said, “please look forward and notice that tree”. When we made it clear of the traffic we soared across the fringe of the Mediterranean. Lightning was peppering the dark water, enriching the free feeling of motion in a warm car seat. Then the supernova of Beirut’s lights exploded onto the blue-black horizon ahead. The cosy scene was only upset by a scabrous shoreline filled with refugee encampments, where grubby children emerged from the mass of rags clothing their mothers. The Middle East’s most recent horror stories seemed to lie just at a safe distance like some cheap ghost ride, always beyond the car window, always too close for comfort.

Amidst the ancient romance of this holy region the sickly neon of Beirut is an uncomfortable site. Here is a real city far from the “Real World”. The desert wilderness gives way to movies and McDonalds, designer pants and pastries. Cranes graze on the rubble of Beirut’s recent hell, excreting glassy piles of contemporary office blocks, coffee shops and places where you can drink yourself into idiocy with thousands of secular revellers who have money to waste. Anyone can fly in for the weekend, party and depart, without ever knowing the Middle East. The bars we visited were just like bars in any other modern city, and full of girls too, who looked like they might even talk to us.

With only a day left away from the office, having a hangover in a city full of blacked-out beemers and mobile phones felt too much like home so, after dropping Al at the airport to fly back early, Joe and I hired a car and got the hell out of Dodge. Lebanon’s deep South is not far to drive to but there are many reminders that you have crossed the travel insurance frontier into No Claim’s Land. The motorways just stop and let you careen into the dirt at 70mph. Banana groves crowd in around the worsening road surface and fresh evidence of machine gun fire and shelling presents itself on the walls of ragged concrete homes which jut out from the trees. The frequency of armed guard posts doubles and doubles again and stray dogs traipse the roadside, howling the recently written story of a sick history.

After driving for most of the night, I tried to get away from the road to find a secluded spot in which to sleep, turning down one of the many access tracks amidst the banana groves. One track ended in a lip curling, stinking mountain of human detritus which was guarded by a swarming pack of skinny dogs. At the next terminus of the next track, our headlights exposed another hut with a machine gun wielding guard. We turned back before he had a chance to confront us, bashing the side of our brand new hire car against a rock and then reversing into a flimsy fence from which hung one of those yellow skull and crossbones signs that I always used to see on news programmes about Princess Diana’s charity efforts. Eventually, we settled for the forecourt of a makeshift petrol station for a couple of hours kip before scuttling away with the dawn light.

Our destination was Qana, a UN camp destroyed by shelling from Israel in 1996. Over one hundred Lebanese civilians and UN representatives were killed and the site was left untouched after the bodies were removed. Now a quiet memorial of crumbled concrete and twisted steel remains, the centrepieces being a rusting Israeli tank and the windowless wreckage of the main hospital building. A museum has been constructed next door, on the site where the curator once lived with his now perished family. He showed us around the bombsite and the museum, pointing to corners of exploded rooms and pinned-up photographs saying, “I lost my brother in there,” and “that is my sister in the picture”. In the print his sister’s charred, faceless body was being pulled from the mess of broken glass and rubble. He introduced us to the remainder of his family, who smiled and gave us bottles of Coke. There was nothing to say.

Children playing by the ruins of the UN camp, bullet holes behind them.

While the parched earth has lain drying like a carcass, crumbling in the sun for millennia, the region has not been able to sit back and watch. Empires have spilled over this land, rising into the hot sky only to be pulled down and rebuilt in some opposing image. Many have tried to conquer this inhospitable land and only some have succeeded so the game can still go either way. For the objective explorer there is still, if he gets in quick, a clear view across the desert into the true heart of the Middle East. Ancient majesty, committed religion and boiling politics thrive very close to the surface and, if it were not for such incongruous strongholds of western modernity such as Beirut, it would be hard to imagine the mournful howls, of the priests in their towers or the dogs in the streets, ever being silenced.

Leave A Comment