Note: this is one of two unusually long posts covering the six months we worked at Buena Vista Surf Club. If I was ever going to finish it, let alone keep it to a few pages, I had to let a lot go. There are many stories and people missing (you know who you are) but I had to be realistic with the time available. This piece is dedicated to Marc, Mariëlle, the guys and girls who keep Buena Vista going, and all the beautiful people around Playa Maderas who made us part of their tribe. And to you, Sergio – el hombre, el mito, la leyenda.

Introduction: a Snapshot from the Lodge

Extract from my journal, written at the time in early 2015:

Here we are – me and my lady, Maeve – volunteering as Co-managers of Buena Vista Surf Club, just back from the beach at Playa Maderas, a short drive north of San Juan Del Sur, in the southwestern corner of Nicaragua. We’re at a kind of peak right now, being the most fit and healthy we’ve ever been, exercising and eating fresh food every day, before crashing-out early and rising early again the next morning. Living with the sun. We are buoyant but chilled, we have a clear structure to our daily lives that is simple and familiar, with just enough surprises to keep us sharp. We live in bare feet and shorts. We walk tall from the yoga and strong from the surfing. This is normal life now. It feels like it has been this way for years. It feels like it could last forever.

We alternate duties with another European couple, each taking two consecutive morning shifts from 07:00 to 14:00, followed by two consecutive evening shifts from 14:00 until late. Each couple gets one full day off every other week. When our alarm chimes at 06:45, the discomfort of waking is brief. We’re soon standing on our bare feet, which have spread out now and feel like they will never fit inside a pair of shoes again. We shower in the en-suite, then grab T-shirt, shorts, keys, done. The local girls are in from 06:30 and carry the vast bulk of the workload, cleaning the hotel and preparing breakfast. We supervise and ensure the guests are enjoying themselves.

From 07:30 Maeve is out on the deck, leading a few of the guests in a morning yoga session, as our local howler monkey troop makes its raucous morning migration through the treetops beside them. Breakfast is a multi-course feast at 09:00, with fresh fruit, eggs, toast and, depending on the day, either pancakes, omelettes, french toast or porridge. All that is washed down with fresh juice and endless mugs of rich coffee from the highlands a few hours away to the north.

If there are any takers that day, I’ll teach them to surf down at the beach after breakfast. Maeve amuses herself with little duties up at the main lodge and, by the time I’m done it’s almost lunch and we’re ready to hand over to the other couple. We eat leftovers, of which there is almost always plenty, swap notes with our colleagues – and the 14:00 shift-change has come around in a blink.

The afternoon shift mainly consists of cooking dinner for the guests, which is the biggest job we have. The cooking is daunting but it’s fun, and we have yet to make any serious mistakes. Our fear is mostly due to our location. The nearest shops are down in San Juan, separated by 25 minutes of bouncing down broken dirt tracks, and in any case the shops would be shut by the time a problem arose. The kitchen is well stocked for cooking and flavouring but not for principle ingredients like meat or vegetables, which we buy fresh. So we have to focus and get it right. That feels good.

We eat breakfast and dinner with the guests, all seated round a huge table, handmade from guanacaste, a local wood, coated in marine-grade varnish so we can throw down hot teapots and dew-covered beer bottles without worry. The couple that is on cooking duty that night sits at the head of the table, announces what we are eating then we fill ourselves with delicious fresh food. The conversation bounces around until well after dinner, then the guests dissipate into the surrounding lounge space, forming small clusters of people who had never met before they arrived but are now becoming friends. We all serve ourselves at the bar, noting down our drinks and snacks on bar sheets, to be tallied-up at the end of the stay. We join the guests, having a beer or two nearly every night. Once every couple of weeks we find some excuse for celebration and drink more, adding rum mixers and wine. But typically we are in bed well before eleven, calm, happily tired. Often as I fall back on the bed and let the day’s constant but steady activity fall off me, I’m overcome with the thought that right now, just now, our lives are wonderful. We feel very lucky.

Guests propping up the bar

After a change, everybody gets used to their new environment, and they do so quicker than they imagined they might. I’m not sure we even had a chance to appreciate our surroundings at the start, as we arrived at Buena Vista with the intention to work, focused on doing a good job and handling any challenges. Then, in the downtime, we have to remind ourselves where we are. We’re not at work, we’re not in the West – this is Nicaragua, in central Central America, far from anywhere, far from home. The sun shines and the waves roll in every day. Latino music drifts on the wind with the barbecue smoke, while chickens and dogs play in the road. This is Nicaragua, our new home. This is the reality that used to be in our dreams, that’s now more real than we expected yet hard to accept. We struggle with it, and then, in the sweeter moments, remember what it is. We look at each other and share a knowing smile, one of us throws a gentle punch at the other’s shoulder, then we both turn away towards the sun as it falls once more on the Pacific horizon and, for a few minutes maybe, we really feel our place.

How did it get like this?

Line-up

The remainder of this piece was written retrospectively, from an increasingly cool and grey autumn in Belfast.

It was back in May last year when we got the email offering us the job at Buena Vista. It was Maeve’s birthday. After dancing around the living room in celebration we were soon dazed by the concept that we had four months ahead of us to learn how to teach surfing and yoga, speak Spanish and cook for 20 paying guests. We only had a basic working knowledge of each of those skills. I started building a YouTube playlist immediately. Soon our pale bodies were stretching and popping on the kitchen floor, as we watched online yoga and surf tutorials. I downloaded Spanish audio lessons and worked my way through them whenever I wasn’t using my brain for something else. I could be seen cycling through the windy Belfast streets in my near-hipster work clothes, brightly coloured socks tucked into purple trousers, talking to myself in wheezes of heavily accented Spanish: “Un habitación doble para dos personas, por favor”.

By the time we arrived to start the job in late October, we felt underprepared but we were confident, knowing that success wasn’t going to come down to our technical skills so much as our characters. We were treated to a soft start anyway. When we arrived it was the lowest point of the low season and the hotel was closed. It would be a week before we would need to cater for any guests. To occupy “the girls” – the team of local maids – and maintain a sense of continuity, we acted in many ways as though the hotel was open. In the morning for instance, the girls would serve a full breakfast just for us two couples. It was embarrassingly luxurious. One morning in particular, after a party at the neighbouring hotel, Maeve and our colleague Ciara were both too hungover to eat so me and the remaining manager James were left to lord over an absurdly large feast.

We slipped into our duties swiftly, it wasn’t difficult. As long as we frequently referred to the checklists we were given, all we needed was a little nous, drive and charm. Buena Vista was such a laid-back and socially oriented venue, that the guests tended to be pleasant by default. Added to that, the hotel was located by a remote beach in a corner of the country, well out of town and up a steep dirt track only accessible in a 4×4, so you already had to be adventurous to want to go there. The guests became instant new friends every couple of days. And as long as we didn’t forget any tasks on our daily lists, or start to cook dinner too late, we were fine.

The hotel practically ran itself, such was the simple and well-trodden system that the owners, Marc and Mariëlle, had instilled. Perhaps the most challenging aspect was communicating with the girls. Maeve’s Spanish was basic but sufficient, while mine was still very raw. The girls didn’t speak any languages besides their colloquial Spanish and as a result probably couldn’t sympathise with the communication challenge. Besides, they had to put up with the frequent turnover of privileged white couples telling them what to do with the eloquence of a four year-old. But not only did we develop friendships with them eventually, we found ways to communicate on mutual terms. Our primary weapon in that war of attrition was base humour, making jokes about sex, genitalia and cursing. Nothing levelled the playing field better than pointing at your crotch and shouting something obscene.

We took to our teaching jobs with surprising ease. Maeve was to lead the morning yoga and I was to teach surfing. We performed these tasks in turn with the other couple, depending on who was on duty at the time. Occasionally, groups from yoga studios in the States would book the entire hotel for a yoga retreat, bringing their own teachers and therefore not needing us to lead the sessions. Two of the first three weeks we worked there were booked-out in that way so we got to sit-in on the classes and learn from experienced yoga teachers. After that, Maeve was taking her own sessions in the mornings with rapidly growing confidence. I was soon comfortable with the surf classes and taking them on my own within a few days of starting, but the story of my surfing has its own place elsewhere.

We expected that we would have physical lifestyles out there but the reality was even better than we had hoped. Daily surfing and yoga was complimented by working on our feet, physical jobs like cooking, and frequent yomps up and down the steep dirt track between the hotel and the beach. We started to get fit immediately. But we couldn’t put our fitness regime down to diligence. The truth is, there was little else to do. And somehow that was great. Life had been simplified. We no longer had the anxiety of options, just a handful of rewarding daily distractions. And the waves, well, there was no excuse to be out of them. So we got fit by stealth, never pushing ourselves through an exercise regime so much as our bodies were pushed by the nature of our daily activities. We were eating well and drinking moderately. Health, strength and wellbeing were the default.

As our bodies trimmed down and hardened into new shapes, our minds also changed state. The responsibilities of our new jobs were uncomplicated. Everything was in front of us, in our hands. We had no TV, no town life, no circle of friends. The internet service was at best slow, if not down for days at a time. We only had a full day off every two weeks so there was little opportunity to stray far from the hotel. In short, we were serving a half-year stretch in the world’s most pleasant jail. Of course, the pernicious creep of cabin fever would sometimes infect us but we could usually rinse it off in the merciless surf, before medicating ourselves with a sunset cocktail on the beach. We could have let it get to us. We could have become listless, losing love for the lifestyle. But instead we let go, accepted our temporary custody, and in doing so we discovered the mental serenity of surrender.

Our Family

We couldn’t have asked for better employers. It shouldn’t have been a surprise that Marc and Mariëlle would turn out to be good company, considering how they had got to where they were. They had left comfortable homes and good jobs in Holland, to pursue some undefined venture in Central America. Only a couple of weeks after arriving, they decided to buy the patch of land that would become Buena Vista Surf Club. At the time it was woodland with no line-of-sight to the water. By the time we arrived, ten years later, there was a large wooden lodge jutting into the treetops and overlooking the ocean, with a prominent deck that hovered over six sumptuous cabañas, a little one-bedroom “casita” and a self-service guesthouse. They had also built their own family home, in which to raise their two young boys, all in close proximity on the same hill.

Mariëlle and Marc joining us and the guests for Christmas breakfast

There was a Whatsapp conversation between us, our fellow couple and the two owners, that rolled on through every day. Issues and resolutions would be punctuated with stupid photos and insults, and Marc incessantly asking “How are the new guests, cool?” It meant everything to Marc and Mariëlle – even as they tried to live outside the walls of the hotel and raise their family – that the guests were still giving the place the friendly soul that it had become known for. Sometimes they would join us after dinner, or take a shift to give us a break. They would chat with the guests, answering the same question every night, about how they built Buena Vista. Watching them, I wondered what it was like when the place was new and the whole adventure was still ahead of them. Back then, Marc and Mariëlle slept on the floor of the tiny space that was now the office, not knowing if their investment would pay off.

The local staff primarily consisted of the four girls and two resident maintenance men. The girls became characters in the daily theatre of the hotel. Their moods could determine how well the day would play out. Everything was drama, from cruel in-fighting between each other, to delightful afternoons singing together in the kitchen as we prepared dinner. When they weren’t lucky enough to get a lift, they would walk over the hills in the hot sun, from their simple, dirt-floored homes to the hotel. Their lives seemed vastly distant from ours even though we were in the same country for a while. But when we ate out together, or played with their children, or talked about the world together, we became close. Although the local staff barely shared a word with the guests, they were the beating heart of the hotel.

Mario was our main man. A rare find. The stuff of legends. He had stayed with the hotel after assisting with the original build, and managed its maintenance ever since. The hotel grew from his hands, it was his child. He crafted and polished the acres of shimmering local wood that comprised the furniture and walls. If something broke, he didn’t just replace or repair it, he made it better, crafting new parts customised to the task. He was a magician, yet he was also as human and open as could be. Mario was taking weekly English classes but had already got comfortable with the language so we were able to connect with him more than any other local in the country. When he walked onto the site, the dogs leaped in joy around his ankles and every member of staff smiled at his arrival.

Being in one place for six months, with limited mobility, allows plenty of opportunity to make great friends. Those who lived there permanently, like the hotel owners and staff, or the family that ran our favourite taco shack on the beach, were used to the transience of visitors like us. But we knew we had made special connections with them when we finally had to leave. It was hard to walk away from their daily company and they were sad to see us go. And as for the people we worked with in that little paradise, there’s too much to be said. I’ve barely mentioned the couples with whom we shared our jobs – James and Ciara in the early months, then Zweder and Willemijn in the second half. I’ve always focused my travel writing more on places and things, and the beauty of the world, than the people that enriched our lives while we were out there. I don’t have the time or the articulacy to write the portraits they deserve.

The guests brought a different kind of relationship. They came and went like the waves, always there but always changing, with us standing powerless in the drift of their travels. Many became swift friends before they moved on. Europeans and North Americans, with vastly different stories. A geologist, a restaurant owner, a yoga teacher or a music promoter. Honeymooners seated besides guys who had left their wives and kids at home for a few days’ lone surfing. After dinner, when we were full and feeling the weight of the early tropical darkness, it could be hard to join the group and make conversation but as soon as we did we remembered the joy of sharing stories with unfamiliar people.

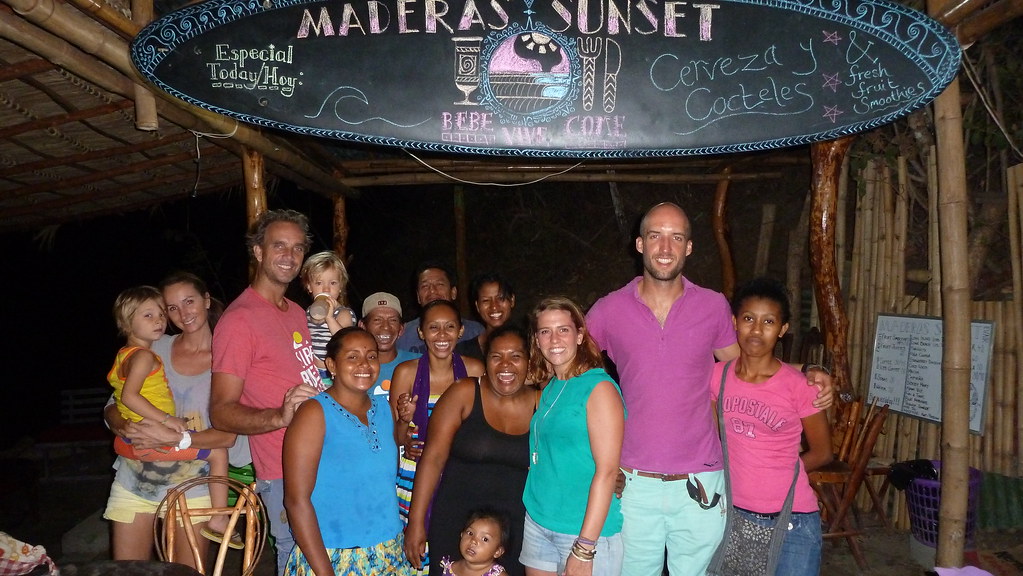

The whole crew apart from our fellow working couple, on our final meal together

…and Other Animals

Living without solid walls, in the wild world of the rural tropics, dawn was a thing. It meant something. We rarely experience dawn in any meaningful way back in Europe, in an office life. The rare joy of a sunrise marks a special moment in our lives, when we’ve stayed up all night or arisen early for a memorable reason. But at Buena Vista, there were many sunrises, they were part of the daily cycle. At first light, a few surfers trickled out into the glassy water, sometimes with us amongst them, as the birds and insects began their songs. But the most prominent voice of the dawn came from the howler monkeys.

“Howler” monkeys have a confusing title. The sound they make is something else, I wouldn’t call it a howl. It’s a guttural, abrasive roar. When we hadn’t forewarned new guests, they would sometimes wake to the noise and ask us what kind of animal could have made it. Dogs? Gorillas? Tigers? One even suggested that there were machines out there. We would tell them that what sounded like demon hell-hounds was just a troop of cute little velvet-furred monkeys no bigger than cats.

The monkeys were a near-daily treat, a welcome distraction for anyone trying to focus on their morning yoga. They would be accompanied by inquisitive urracas (blue-throated magpie jays) and squawking parakeets. A scorpion would skitter out from behind a drying towel or a door frame, bearing its pincers like a keen street fighter. After nightfall, the scent of skunk spray would occasionally drift into the lounge – a sweet mix of urine and burnt hair that was foul but not quite repulsive, unless you were very close to the source. A praying mantis might creep across the bar and climb to the top of a wine bottle, front legs cocked like Nosferatu, before slowly, creepily turning its bug-eyed head towards a nearby guest, then suddenly diving head-first into them and flying away.

While it was still nesting season for the turtles – approximately September to December for the more common Olive Ridley species – we sometimes took guests to a protected nesting site a little way south of San Juan. The beach at La Flor is a wide, gently angled sweep of golden sand, fronted by trees and grass, with no buildings in sight. On the night I visited, the sky was thick with thunder clouds, filtering the moonlight down to a feint glow and sporadically illuminating the whole beach with flickers of lightning. We stalked the beach with our torches turned off to avoid disturbing any wildlife, until we stumbled upon a dark hump in the nearby sand. Then we would watch the mother turtle drag her bulk across the beach, dig a pit, lay her eggs, cover them with sand and return to the water – slowly but tirelessly performing her duty.

Releasing baby turtles on the beach at La Flor

In the middle of the afternoon one day, long after turtle season was supposed to have ended, Maeve and I noticed a crowd gathering on the beach. We were out on our boards in the line-up but word reached us that there was a turtle nesting in the sand, amidst dozens of partying tourists. By the time we reached the shore, the crowd had moved, having shuffled in a slow circle towards the water as the turtle made her way back. Then the circle opened and the turtle waddled through the gap and out into the surf. For a few seconds I alone was paddling alongside, me on my board and her just below the surface next to me. But she soon accelerated and vanished.

During the day, we would gaze out over the deck towards the distant ocean. There would be a sudden flash of white, probably just a wave breaking in the distance but worth grabbing the binoculars and watching for a while, just in case. Usually it was nothing. Occasionally the white speck would flash again, and hang in the air before slowly fading: spume from a humpback whale. Then, a couple of fortunate times, we were treated to a display of fin-slapping and breaching before they disappeared again below the impenetrable blue surface.

In a single week we had two memorable wildlife encounters. One night, Mario told us that he had seen a sloth crossing the road a couple of hundred metres away down the hill. With the rest of the guests, we gathered torches and sandals to go and see it. Nobody rushed. By the time we arrived, the poor creature was still only another small fraction towards crossing the road. One of the guests, Ashok, sat down beside the sloth, rum mixer in one hand, and stroked its head with the other. It was too slow to protest effectively. Then Marc carried a large branch over and the sloth gripped it with surprising strength, swinging upside-down to hang from the branch as Marc lifted it to safety.

Ashok petting a wild sloth

Marc taking the sloth to safety

The other animal incident that week was a little more dramatic, although it will never be translated effectively into writing. You had to be there. Just try to imagine me and a battle-hardened US Marine, huddled in an outdoor bathroom in the middle of the night, peering through an open section of wall at the neighbouring cabaña, where Maeve and the Marine’s roommate – Ashok again – were defending the cabaña from a siege that resembled The Wall from Game of Thrones. One of them was dangling a broom out of the open section of the cabaña and swinging it wildly in an attempt to knock the attacking creature off the outside wall. All the time, no matter what efforts we made to repel it, this thing, this alien, prickly skinned rat-dog thing, just kept crawling relentlessly back into the cabaña. By the time we finally ousted it – in a brutal counterstrike led by our Marine friend – we were crying with laughter. It later turned out to be a (reasonably) harmless Mexican porcupine, but who were we to know?

A Good Ride

Once well into our tenure at Buena Vista, the life of the hotel had become our lives, as if there had never been another way. Home and jobs and cold nights by the fireplace were a universe away. But so too was the backpacking adventure we had been enjoying only as recently as October. Most of the time in the hotel we were treading water, lost in the daily flow, occasionally climbing to some unexpected peak of experience but soon drifting back down again to a base level of comfort. Our free day only came around every two weeks, but when it did there was an opportunity to throw ourselves back into the nomadic wonder of the foreign land in which we had become so comfortable.

On one exceptional day off, we rented a car from “Irish John”, an expat friend of the hotel who, improbably, came from our familiar city of Derry. He gave us directions to a mechanic in town to collect our vehicle. There, we were confronted by a gnarly fingered old man and his assistant, in a small lot with just enough space for three cars. He took us out onto the street and showed us our ride. It was a bright red Toyota Land Cruiser that had been driving around for longer than we had been alive. There was no roof besides a slip of ragged black canvas, and the interior was a bare cockpit of exposed red metal, dials and wires. The mechanic showed us how to start the car, which involved pulling a little plunger out from the dashboard, like some Industrial Revolution-era machine. There was a little plaque with diagrams that explained the four-wheel-drive system. I squinted it at it, trying to read the worn etching. But the mechanic told us not to bother with four-wheel-drive. There was no need, he insisted. He slapped the door and yelled, “Es un mulo!” (“It’s a mule!”)

Once we were on the main road, headed north to an unvisited part of the country, Maeve gave me a cynical glare from the passenger seat. I was driving the car as if I was trying to navigate a slalom, wildly swinging the wheel from side to side. “What the hell are you doing?” she asked. I just kept staring at the road in front and replied, with a smile, “Just wait ’til it’s your turn to drive it”.

The old Toyota was a tank. It growled as it gradually built up to full speed, and wobbled under its absurdly loose steering. When Maeve took the wheel she soon laughed as she understood why I had struggled to keep it in a straight line. I jumped in the back and stood up, gripping the roll bar and grinning into the warm breeze. I ducked for branches while Maeve swerved and bounced through ruts and rock piles.

Maeve in command of the tank

Selfie, standing on the flat-bed and feeling the warm air

After visiting a couple of beaches to the north of our home, in the area around Popoyo, we were starting to run out of afternoon. The sensible choice would have been to turn back and race the dying light but we couldn’t do it. We just kept pushing further north, until we were watching the sunset from some remote beach, as squadrons of pelicans skirted the violent, shimmering surf. Then we made for home. The light was already too dim for Maeve to drive confidently without her glasses, so I had the whole journey ahead of me at the wheel. It was soon utterly dark and I was squinting into a pool of headlamp light that would have been no worse if we had just had someone running ahead of the car holding a candle. My nose was almost in contact with the windscreen and my knees were either side of my ears. For two and a half hours. But we got there. We even stopped for a while in Rivas, about forty minutes from home, where we joined the locals in a raucous Christmas street party.

Western sensibilities could have made that day trip seem frightful or reckless but it was just old-school adventuring. That car was a rickety chariot for a pair of explorers who wanted to smell the sweet tropical air and feel every bump in the road.

The Climb

So went those six months of elemental living, in the daily repetition of hospitality, exercise and amusement. At first, when it was new, it was exciting. But there was a time between the initial novelty and that blissful calm I described above, when I couldn’t quiet my brain. I was convinced that I needed to be more productive, to use my free hours to work on some of my nebulous “projects”, that had for years haunted my mind. They were like the ghost of a future me, who was guilt-ridden at not having made “better use” of his time. I dabbled with a few ideas in quiet moments but the sun would keep falling into the Pacific and the days would drift away from me, carried by the immediate distraction of good people and a warm outdoors.

The first big mental breakthrough came a couple of weeks into our tenure at the hotel. A yoga group had rented the whole place for the week and we would join their sessions in the early mornings and late afternoons. Reflecting on the six months that we were there, and the dozen-or-so yoga groups that came through, a special few of the group leaders will always stand out in our memories. Each of them was influential for different reasons, unique to their personal styles. Marlene was the first to get to me. Her exceptional style was characterised by the way she straddled the edge of yoga’s spiritual side without a hint of bullshit. There was a humble fluency in her voice that gave us the confidence – the permission – to throw ourselves into the meditation of her words.

As we stretched and balanced and breathed, out there on the warm deck, floating in the treetops, on a level with the monkeys and the magpies, Marlene led us out of ourselves. I felt weightless – in body and mind. I closed my eyes and tried to find myself in the world, suspended as we were a few metres above the soil of a remote spot on the edge of an unfamiliar continent, somewhere between the world and the sky, and very far from home. In that bliss, some other ghost of me visited. But this was a spectre of now, not some unknown future. This ghost was content and confident, telling me it was OK to be happy, OK to forget who I may have been or may someday be, and just to grow now, in that place, up there in the morning air. I had gone to Nicaragua looking for peak experiences that would remain somewhere in me for life, and those morning sessions became one of them.

Yoga on the deck

Yoga, surfing, playing host to paying guests, cooking for a crowd; many aspects of our sun-filled lives benefitted us in their own ways. I could look back and barely discern the path along which I had been advancing, but I knew I had got somewhere good, and was headed somewhere even better. Those early moments of yoga-fuelled euphoria marked one of the little milestones along the way. Another came much later, in late January, around the middle part of our stay, when we were perhaps at the nadir of our motivation and cheer – still happy but slightly listless and disengaged.

At that time, two of Maeve’s friends had booked a cabaña at Buena Vista for the week. Pia and Olivier are a French couple, who live in Mexico City, running a business importing cheese and wine from their homeland. Olivier is pensive, measured, he knows what he likes and wants, yet he is laid-back and open to all things and people. He became my consultant. One afternoon, I was explaining to Olivier my frustration at wanting to work on my projects while there was time to do so, yet never knowing which one or ones to focus on. Olivier almost scolded me, as if I was being idiotic. “If you don’t know what you want, stop thinking about it. It will come. Right now, just enjoy what you have in front of you”. It was the kind of counsel I might have given someone else but couldn’t apply to myself. I’ve heard that “wisdom is following your own advice” but sometimes it needs to come from the outside. Of course he was right, I needed to make the most of my time there, to live in the now. But I couldn’t wholly agree with his sentiment. I didn’t want to live aimlessly forever, never building anything for myself. Then again, having come that far with no real progress for my “projects”, I couldn’t argue with him. With a doubtful shrug I agreed to the plan.

Starting the next morning, my focus of meditation was on nothing. Nothing but the moment I was in. No future, no projects. The weight of anxiety fell away and I became a delightful emptiness, like I had been back in those yoga sessions a few months earlier. Then, perhaps only three days later, I awoke with a clarity of purpose that I had never felt before: a single project that I could apply myself to with passion and vision. This is not the place to explain the details of my idea, only that I had one. Just one, and it stuck with me for the rest of our stay, and the adventures that followed, and into my life back in Northern Ireland. It gave me a single heading to steer for, and a strength of purpose that woke me early every day, gave me energy and drive. That time too, was a kind of peak. Thanks Olivier.

The Drop

In our final week there was a run of lasts: last meals, last surfing sessions, last times doing specific jobs. We ate out for the last time with our colleagues on Tuesday, the owners on Wednesday, and with the rest of the hotel staff on Thursday. When it was our turn to do the evening shift we picked two of our favourite dishes to cook for the guests – falafels from the Middle East, and stuffed papayas from the Caribbean. By then the cooking was an easy routine.

With each day the strength of our feelings for departure grew. Those feelings were mixed between two extremes. We didn’t want to leave such a simple, healthy, happy lifestyle, but we were itchy to be free again, starting fresh adventures.

We shopped for the last time, making our regular rounds of the supermarket and other shops in town with the efficiency and ease of six months’ repetition. The car park attendant at the supermarket wished us luck and waved us out of our parking spot for the last time. We had lunch in our regular haunt, Barrio Cafe. For the last time, we ordered our regular coffees and some food. It was Maeve’s turn to drive so she had the pleasure of the final run in the staff car, a Land Cruiser that leaped and lurched like a young goat over any wretched road we threw it at.

The beast-of-a-ride that the Buena Vista staff got to use

The pressure and moisture in the air had been building for a few weeks, as the rainy season approached. Through the early months we had enjoyed cloudless blue skies and perfect clear nights. But as we got ready to leave, the sky became hazy and ever fewer stars were visible. Greenery and flowers crept back into the forest around us, even though there had been no rain. We felt the seasons changing and we knew the natural world was sending us away before it turned damp and lush and rains began to fall.

The previous year’s rainy season had ended later than usual. As late as 5 December it was still humid and cloudy, and that day it rained in the afternoon as it had done most days for months. But on 6 December we woke to hot, dry sun and a howling wind that shook the hotel and made an oppressive noise all day. The rainy season had ended instantly. When Mariëlle came up to the hotel that morning she rolled her head to gesture at the shuddering structure around us and casually remarked, “So now we’re in the Windy Season”. And that wind blew, constantly and with frequent powerful gusts, all day for a month. Then, when it seemed to be easing off, it would build again and just keep blowing, on into February and then into March. On a handful of days it was infeasible to sunbathe on the beach. Tourists would try it, lying down on their sarongs with a book for about five minutes before they gave in to the constant whipping of sand against their skin, filling their ears and working its way into their bags.

At the time, down at the beach, we asked our friend Maria when the wind would stop. She said, “It’ll continue like this, maybe get a little stronger, right up to Semana Santa”. And sure enough, after Semana Santa – the week of what we call Easter – it blew for a couple more weeks and then faded rapidly away towards the third week of April. Then, with the new season came the return of the warm water. The wind had previously blown all the heat out of the sea to the point that, on a few days, our feet and hands would get numb and we would leave the water prematurely after shivering in the blasting, spray-filled air. But whenever the wind had eased for even two days the water temperature had soared, hinting at what was coming in April.

When April finally came, bringing those starless nights and that warm, glassy water, our final weeks felt like they existed in some no man’s land between the seasons. We would soon cease to exist in the life of the hotel and another couple would make it their home. They would know a different climate to ours and that would feel normal to them – like it had been that way for years. Like it could last forever.

Our final day, 27th April, was a convenient time to shut the hotel for a week and re-thatch the vast palapa roof. It was also Marc’s birthday. All the paying guests left in the morning and a bunch of Marc and Mariëlle’s friends came round. We made party food, set-up speakers on the deck and drank rum. By midnight the group had dwindled to a handful and the party had morphed into a surreal cabaret of slurring Dutch karaoke. We lay back on beanbags and looked up for the last time. Above us, twinkling in the murky sky, were the same stars that had been there every night before. Each evening, we had stood on the deck and watched the sun set into the water below us, dashing absurd colours across the horizon. Then the tropical night had pounced in, taking no prisoners. The stars would blink on, like the lights of cottages in a winter landscape, welcoming their owners home from the fields. That’s the way it had been for 180 nights. Now, one last time, we watched them slide over the dome above us. We would be leaving and they would continue wheeling through the sky without us. The stars just keep coming, that’s what they do. Like the waves, they don’t care.

Sunset from our favourite Taco shack at Playa Maderas

Ben, it was such a joy to meet you and Maeve and OH BOY are you an incredible story teller. Thank you for sharing your journey.

I thought of you particularly when I wrote about the mind-altering yoga experience. You guys were our first! And I have such fond memories of our time together.

Thanks for your kind words. I hope it’s not long before we’re breakfasting again together… X

Brilliant to have those places, people and activities described in such an eloquent way. Lets me re-live it all!

Glad to hear it. “Re-live it”, huh? That’s a good idea…